Editorial note: This is the third contribution to the debate initiated by Michael Greenhalgh in the September 2006 issue of the 3DVisA Bulletin. Here, Daniela Sirbu gives her response to the question raised by Greenhalgh, Will computer models ever get better?

BEYOND PHOTOREALISM IN 3D COMPUTER APPLICATIONS

Daniela Sirbu responds to Angela Geary and Micheal Greenhalgh

The fascination with the illusion of reality in visual arts has waned with the advent of photography and cinema.1 Although various forms of realism have been always present,

a resurgence of the interest for creating representations as illusions of the physical world has emerged in relation to 3D computer graphics during the last two decades of the 20th

century. It is not surprising to see that photorealism in 3D graphics has surfaced on our discussion forum with the first two issues of the 3DVisA Bulletin through the articles of Michael

Greenhalgh and Angela Geary. So far, the discussion revolved around the 3D computer

reconstructions of existing historical architecture or existing museum artefacts.

I shall try answering some of the intriguing questions raised by Michael and Angela regarding the possibilities and limitations that 3D computer graphics if we take photorealism as the main criterion for evaluating the artistic production in this area. However, I would like to first raise some questions that fall somewhere in-between the positions taken by Michael and Angela. I am asking why focus on photorealism when no true photo camera is involved? Why not speak about realism instead? And if we bring realism into discussion, do we still speak about the same things with reference to the 3D computer graphics medium as we do when we speak about photorealism?

The term realism comes with a number of interpretations previously acquired in visual arts, literature, and film. As the term frequently appears in this article, I would like to clarify that it refers to emulating the natural world in the medium of a 3D computer environment where all our senses, and not only the visual sense, are involved in the perception of the illusion of the physical reality.

Photorealism and Realism in 3D Computer Graphics

There are at least two aspects that underlie the concern with photorealism and realism in 3D computer graphics. One aspect is how new media is situated in relation to other media and the second aspect is how new media, in particular 3D computer graphics, operate in the production of content.

In accordance with Bolter and Grusin’s theory of remediation,2 the new emerging media have always remediated older media. An example that

comes to mind is the remediation of the theater and of the novel during the emergence of film as a new art form. Until grammar of the film language has been established,3 responding

to specific needs of film as a distinctive form of artistic expression, the older media have been strongly felt in film with all inconsistencies that result when one tries to

operate with the means of a given medium into another. A general analysis of the digital media genres shows that the remediation of older media in the emerging new media is just

a particular case of the general phenomenon of remediation. So, what are the older media that 3D computer graphics remediate? Answering this question, which I shall do later in

this article, helps us understand where 3D computer graphics and our fascination with photorealism are coming from.

On another hand, we must not forget McLuhan's well known argument, 'the medium is the message'.4

It captures the idea that while we improve and come to intimately understand a medium, we also select and adapt the content to what the medium can do best. This goes up to the point where the

content and how it is conveyed is dictated by the medium. When the medium is mature and used at its best, it becomes invisible for the audience. And while the audience is fully engrossed with

the content, it is the medium that operates and the perceived message is very much its child. These are the issues that we face when a given medium becomes mature. Understanding where 3D

computer graphics has arrived in relation the 'medium is the message' problem may help us foresee to where the domain is heading.

I shall briefly discuss below photorealism in relation to the phenomenon of remediation in 3D computer graphics, and what realism entails as the medium of 3D computer graphics matures.

Remediation of Photography in 3D Computer Graphics

We turn now to the question posed earlier: What are the older media that 3D computer graphics remediate? As 3D computer graphics emerged together with a renewed interest for creating representations as illusions of reality while most of the 20th century visual arts shifted away from this trend, we are inclined to look towards photography and film. These are two significant cultural forms of the twentieth century and both are based on recording reality. Representation artefacts derived from the utilization of photo and video camera recording techniques are emulated with 3D content creation programs. We can see digital simulations of filtering, blurring, lens distortions, camera focusing and other representation artefacts, which are typical for the real photo and video cameras. While all these refer to the final output, we sense that there is still a deeper interconnection between photography, film, and 3D computer graphics explaining why a focus on photorealism emerged together with the domain of 3D computer graphics.

This deeper interconnection between photography, film, and 3D art is related to the content itself, which is recorded reality in the case of

photography and film. In the case of 3D computer graphics, the content to be recorded is produced based on the perspective representation system as employed by specialized 3D

programs.5 Having the challenging problem of perspective automatically solved by the computer, the creation of representations as

illusion of the real world is significantly simplified. The perspective representation system was heavily employed by traditional media – painting and drawing in particular – when

the fascination with creating the illusion of the physical world was still dominant. The emergence of 3D computer graphics based on the perspective representation system in the

production of content has naturally found immediate connections with photography, film, and with the traditional painting and drawing as mainly practiced before the advent of

photography. If we take a closer look, we can see that photography and film also remediate painting. It is a well known fact that most of the time simple recordings of raw

reality with the photo and video camera are not satisfactory unless these are well plotted by the artist. These unprepared recordings may appear to be cluttered with unwanted

details, losing much of the sense of depth, and sometimes we may have a hard time understanding why things look so different from what we remember about the real thing.

To acquire in photography and film the qualities we are looking for we have to operate on what is going to be recorded in the shot. Behind the eye is the mind that organizes what we see discarding detail and focusing on what is important at the given moment. Behind the camera is the artist working with light, distribution of tone and color, size relationships, and a myriad details in his attempt to give us an organized and meaningful glimpse at the real world through the picture recorded with the camera. The concepts that the photographer operates with are very similar with those of the traditional painter, although there is a whole world of specialized concepts that are specifically related to either photography or painting. In order to acquire that meaningful shot, the photographer must understand how things work in real life. We expect him to have the training of looking, analyzing, and understanding what surrounds us, and than give us back his understanding through the means of his chosen medium. This is a training that artists have always had, and it is what we call the studio experience. It is where the artist is trained how to look at the world and where he learns the specifics of the particular medium he is working with.

Coming back to 3D computer graphics, we have to look at the artist behind the technology just as much as we look at what technology can do at a certain point in time. The 3D artist shares a common type of experience about looking at the world around us like the painter and the photographer. There is a common art vocabulary they share and there are some very specific aspects that characterize the 3D graphics medium alone. Working with light and color has a different logic in the digital medium than it has in real life, in painting, or in photography and film. However, the experience coming from these older and thoroughly known media is very helpful.

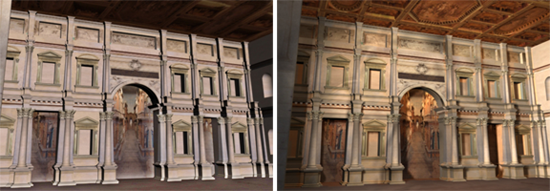

Fig. 1. Digital reconstruction of Teatro Olimpico designed by Andrea Palladio. The two renderings illustrate the effect of different lighting

schemes applied to the same 3D environment. 3D reconstruction (work in progress) by Daniela Sirbu, Virtual Reality Lab, University of Lethbridge, Canada. Reproduced by kind permission.

From the close interconnections established in the process of remediation between the medium of 3D computer graphics and the older media, it becomes apparent why we are often inclined to talk about photorealism rather than realism as an evaluation criterion of the 3D virtual environments. Trying to operate with the means of a medium and emulate its output into a different medium will naturally come with a series of obvious inconsistencies. This might be one of the reasons for which Michael Greenhalgh will always find the photorealistic quality of images produced with a photo camera to be superior in comparison with the attempts at photorealism of images rendered from 3D programs.

The brief analysis of the phenomenon of remediation in 3D computer graphics also brought the artist at the forefront. I find this to be necessary

as most of the discussions usually focus on what technology can do and what we further expect from it. I would only like to emphasise once more that the artist and his experience

in the art practice both traditional and digital are just as important. There are some significant examples to demonstrate that at times when technology was rather modest in what

it could offer as a medium for 3D computer graphics, artists and architects have been able to render excellent photorealistic images from digital reconstructions of architecture.

I mention here Kent Larson’s 3D reconstructions of Louis Kahn's unbuilt architecture6 rendered samples of which are available

online, and Takehico Nagakura's 3D visualisation during design stages of the Gushikawa Orchid Center.

Samples of the rendered images from the 3D computer model and photographs of the final building can be comparatively analysed online.

Beyond Photorealism in 3D Computer Applications

As 3D computer graphics mature, real-time interactivity and immersion become more prevalent features. These give the specific dynamic character of the new medium and are not to be found in photography, film, and traditional art. New media art and applications relying heavily on such features are more difficult to relate to certain older media.

For example, Virtual Reality applications based on CAVE7 and similar systems are meant to create

the illusion of full immersion in the virtual space. Such systems attempt to induce the feeling that the user can actually move around in the computer generated environment, and while the movement happens the environment as seen by the user changes in accordance with the new view points assumed in the space at every given moment. The natural integration of the user within such environments requires working with the entire human perception system and not only with visual and auditory perception. Conveying depth and physical proximity of objects are still based on linear and aerial perspective, but more is needed. Three dimensional sound may help locating the sound source in the virtual space. The surface quality and the hardness and softness of objects are not only seen, but can also be felt through the sense of touch. Specialised haptic interfaces are needed to allow this type of experience. Collision detection is necessary to prevent the user and other virtual inhabitants of the virtual space from going through walls, floors, or other objects. Simulations of real world physics are necessary to emulate the behavior of objects, their weight, frictions, gravitation, and interactions with other objects.

A lot more must be added here, but it is not my purpose to describe such applications accurately or in any detail. I only want to emphasize that photorealism is a restrictive and unsatisfactory criterion in evaluating the quality achieved in emulating the real world inside Virtual Reality environments. The illusion of the physical world as we try to create in such environments must engage all five senses and photorealism is addressing preferentially the visual perception. As we step from photorealism to realism in the sense used in this article, we move closer to the specific core of 3D computer graphics applications.

The degree of complexity involved by Virtual Reality requires a very high level of computer processing power. The current technology does not allow achieving a satisfactory level of realism in any such applications. We still have to wait until we shall be able to explore the true possibilities and find out what is the message of this medium in the sense of McLuhan’s 'the medium is the message' argument.

Conclusion

Examples provided in this article show that a high level of photorealistic quality has already been achieved with 3D computer graphics when real-time navigation or immersion is not required. The artist or architect creating the 3D computer content is as important as he or she has always been when working with other older media. However, we must recognise the fact that although the experience of the practicing artist may often overcome the limitations of computer technology in obtaining high quality graphics, it is necessary to arrive at a certain minimum performance level with technology to allow any degree of acceptable quality to be obtained. Where acceptable quality has not yet been achieved, the most important problem is the level of processing power made available by the current technology. If we look at how computer technology has developed so far, we can be very optimistic about the great potential for better quality in 3D computer graphics.

Notes:

1. Newhall B. (1964), The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day, 4th ed., New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. Manovich, L. (2001), The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p.23.

2. Bolton, J. D. and R. Grusin (1999), Remediation. Understanding New Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

3. Arijon, D. (1976), Grammar of the Film Language, New York, NY: Hastings House.

4. McLuhan, M. (1964), Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

5. Wilatts, J. (1997), Art and Representation. New Principles in the Analysis of Pictures, Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. In my analysis I take into account

Willats’ idea that changes in representational systems reflect the differences in the functions the representation systems are supposed to serve.

6. Larson, K.(2000), Unbuilt Masterworks, New York, NY: Monacelli Press.

7. Burdea, C.G. and P. Coiffet (2003)0, Virtual Reality Technology, Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Interscience.

© Daniela Sirbu and 3DVisA, 2007.

Back to contents