|

3DVisA Resources

3DVisA Index of 3D Projects: Archaeology

Longhouse 3.x

Keywords: Virtual Archaeology, Digital Archaeology, Iroquoian Longhouses, Iroquoian Archaeology, Power, Authenticity, Agency, Authority, Transparency, Knowledge Mobilisation

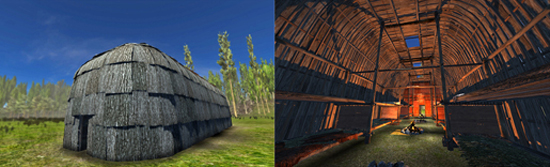

Fig. 1. Longhouse 3.x. High-resolution renderings, in the Autodesk Maya software, of external and internal longhouse test models within Unity5. © theskonkworks incorporated/Sustainable Archaeology/ASI. Reproduced with kind permission.

Longhouse 3.x is an exploration of agency, authority, authenticity and transparency within virtual archaeology. Through the (re)imagination of a 15th-century Northern Iroquoian longhouse, this project explores the entire process from conception to participant engagement of the design, development and implementation of a virtual longhouse. Autodesk Maya was used for modelling. The model was ported to a Unity game engine, in combination with an Ocular Rift immersive environment.

Fig. 2. Longhouse 3.x. Detailed Unity5 gameplay rendering of game resolution 3D scanned Iroquoian pottery and placement of fire/cooking hearths. © theskonkworks incorporated/Sustainable Archaeology/ASI. Reproduced with kind permission.

Longhouse3.x followed a typical film, television and gaming production pipeline adapted for scholarly visualisation. Initial representative archaeological data were collected; visual references were assembled and created, based on available information, and modern interpretations of the assumed similarities for props and texture maps developed. The academic interpretations of the assembled research were then augmented by professional 3D and gaming creative and technical support. The aim was to (re)imagine a typical northern Iroquoian longhouse based on available data and archaeological meaning-making. The project did not aim to suggest a full reconstruction of an actual archaeological site.

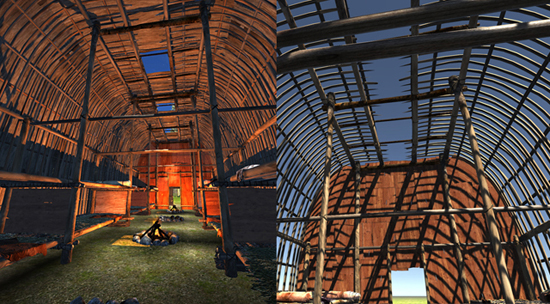

Fig. 3. Longhouse 3.x. Detailed lighting test of the longhouse model with fire, door and smoke hole lighting sources within Unity5. Test placement of upper level rafter food storage. © theskonkworks incorporated/Sustainable Archaeology/ASI. Reproduced with kind permission.

Using collated historical archaeological site data of longhouse excavations in Ontario from Christine Dodd (1984) and cultural historical interpretations of longhouse construction and use primarily from J.V. Wright (1971), Mima Kapches (1990, 1993) and Dean Snow (1997), the initial longhouse dimensions and construction measurements were determined as a base template in the virtual 3D construction of assets for Longhouse 3.x. Knowing the rough historical parameters coupled with the cultural historical, oral, written and visual histories provided a hypothetical mental map of the look and feel of a typical northern Iroquoian longhouse. Assets were built in 3D space, which were representative personal interpretations of the data collected and the ongoing collaboration of stakeholders within the archaeological community. Coupled with recent examples of experimental archaeology and traditional modes of archaeological knowledge creation these representative assets were then assembled within Autodesk Maya and tested for relative fit within the cultural historical norms of longhouse use and construction.

Assets were then migrated to a Unity5 game engine for assembly within a virtual environment. Following Dawson, Levy and Lyons (2011) work on virtual Thule Whalebone houses, environmental phenomenological assets were added. Light, fire, smoke, shadows and sound provided additional sensory elements, which enabled embodied experiences within the virtual environment. Using a standard Xbox 360 haptic game controls users can explore through movement and camera direction internally within the virtual longhouse space and externally within a limited representation of a potential natural habitat. Lastly, Ocular Rift Development Kit 2 head mounted displays provide the opportunity to engage immersively within the virtual environment.

Fig. 4. Longhouse 3.x. Comparison of game (left) and photorealistic film rendering (right) of longhouse model assets. © theskonkworks incorporated/Sustainable Archaeology/ASI. Reproduced with kind permission.

Along with the technical build of Longhouse3.x, the project was designed to explore the Power and Authority of archaeological visualisation from a position of the maker (Ingold, 2011) as well as the agency, authenticity and transparency experienced by the participant (Bentkowska-Kafel et al. 2012; Denard 2012; Earl 2013; Frankland and Earl 2011; Frankland 2010; Perry 2009). Using the London Charter as a template, an accompanying project website was developed to provide pre-project historical referencing and production updates on the design, development and deployment of Longhouse3.x. Social media such as LinkedIn and Twitter is being used extensively to inform and engage archaeological stakeholders and non-stakeholders alike. All responses and comments are public unless requested to be anonymous. As the project continues to progress, course corrections on the visual reconstruction within virtual space, are negotiated based on participant input and project fit.

As this project is currently (February 2016) in the second phase of deployment to archaeological stakeholders, further description of progress will be forthcoming.

Technical details: This project is using a combination of Autodesk Maya and Mudbox for 3D and 2D asset creation and Unity5 for deployment within a gaming environment.

Xbox 360 haptic controllers are used for user interaction and Ocular Rift DK2 headsets for user immersion.

Unity5 was chosen as the platform best suited for multiple device deployment and the ability to handle large user experiences within a single virtual space.

Project dates: Ongoing from July 2015

Resource status: Assets are currently stored at Sustainable Archaeology and theskonkworks incorporated. Digital Internet access of the public facing project research is provided by theskonkworks incorporated. Open Access of assets will be made available through Sustainable Archaeology.

Contributors:

Michael Carter, Radio TV and Arts School of Media and Department of History, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

This project is funded by Sustainable Archaeology, The Museum of Ontario Archaeology, Archaeological Services Inc and theskonkworks incorporated. Production done by Polymorphic3D.

Sources, links and further details:

- Bentkowska-Kafel, Anna, Hugh Denard, and Drew Baker. 2012. Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Dawson, P., R. Levy, and N. Lyons. 2011. “‘Breaking the Fourth Wall’: 3D Virtual Worlds as Tools for Knowledge Repatriation in Archaeology.” Journal of Social Archaeology 11 (3): 387–402.

- Denard, Hugh. 2012. “A New Introduction to the London Charter.” Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities Series(Ashgate, 2012), 57–71.

- Earl, Graeme. 2013. “Modeling in Archaeology: Computer Graphic and Other Digital Pasts.” Perspectives on Science 21 (2). MIT Press: 226–44.

- Frankland, T.J. 2010. “A CG Artist’s Impression: Depicting Virtual Reconstructions Using Non-Photorealistic Rendering Techniques.” In Thinking Beyond the Tool: Archaeological Computing and the Interpretative Process., edited by Angeliki Chrysanthi, Patricia Murrieta-Flores, and Constantinos Papadopoulos. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/203059/.

- Frankland, Tom, and Graeme Earl. 2011. “Authority and Authenticity in Future Archaeological Visualisation.” Original Citation, 62.

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Taylor & Francis.

- Kapches, Mima. 1990. “The Spatial Dynamics of Ontario Iroquoian Longhouses.” American Antiquity. JSTOR, 49–67.

- 1993. “The Identification of an Iroquoian Unit of Measurement: Architectural and Social/Cultural Implications for the Longhouse.” Archaeology of Eastern North America. JSTOR, 137–62.

- Perry, Sara. 2009. “Fractured Media: Challenging the Dimensions of Archaeology’s Typical Visual Modes of Engagement.” Archaeologies 5 (3): 389–415. doi:10.1007/s11759-009-9114-z.

- Snow, Dean R. 1997. “The Architecture of Iroquois Longhouses.” Northeast Anthropology 53. Institute for Archaeological Studies, University at Albany, SUNY: 61–84.

- Wright, J V. 1995. “Three Dimensional Reconstructions of Iroquoian Longhouses: A Comment.” Archaeology of Eastern North America. JSTOR, 9–21.

Project website: http://theskonkworks.com/

Record compiled by Michael Carter, 18 Febbruary 2016.

3DVisA gratefully acknowledges the help of ...... with preparation of this record. © Michael Carter, 2016.

Back to the list of 3D projects

|