FEATURED 3D RESOURCE: SOUTHAMPTON IN 1454: A THREE-DIMENSIONAL MODEL OF THE MEDIEVAL TOWN by Matt Jones

WINNER OF THE 3DVisA STUDENT AWARD 2007

WINNER OF THE 3DVisA STUDENT AWARD 2007

Keywords: Urban studies, Southampton, 1454, visualisation, 3D computer model.

This paper is concerned with a project whose aim was to create a three-dimensional computer model of medieval Southampton in the year 1454. This particular year was chosen as there is good documentary evidence for the town's layout and good archaeological evidence for various elements of the town.

The choice of such an exact date is due to the existence of an important document, dated to 1454, known as the Southampton Terrier. This document lists and details all rent-paying properties in the

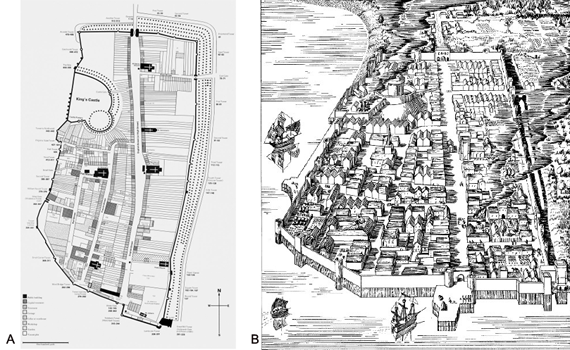

town. It was used by Burgess in the 1970s to produce a town plan (Fig. 1).1 The finished model will be exhibited in the Museum of Archaeology, Southampton.

Fig. 1. Medieval Southampton. A. Plan based on the Terrier (Burgess, 1976). B. A conjectural illustrated reconstruction of the late medieval town (after Platt and Coleman-Smith 1975:29).

Three-Dimensional Modelling and Archaeology

Three-dimensional modelling is a very useful tool for the discipline of archaeology. Traditional dissemination techniques leave the vast majority of archaeological projects under-appreciated.

Archaeological discoveries and excavations rarely find an audience beyond those who read the excavation reports. Although not specifically designed to alienate the general public, Hermon and Fabian criticise traditional excavation reports for their linearity, limited use of recovered data and technical focus.2 The technological advances of the past two decades have facilitated the growth of computational modelling techniques. Driven by a demand for more accessible software, a vast array of desktop programs have been developed which allow for the creation of such models.

The community-driven focus of the internet of the past few years has gone even further to make such software accessible; open-source software providing cost-free alternatives to, often expensive, programs, as well as facilities for ‘trouble-shooting’. The community aspect of this form of software development also provides resources for learning. With such opportunities available it is inevitable that models representing aspects of the past will become more widespread. It is important that the discipline of archaeology engages with this ever-growing community and makes full use of what computational models have to offer.

Of interest to this work is three-dimensional modelling. Proceedings of the Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA) conferences and British Archaeological Reports (BAR) prove that a section of the archaeological community is validating the use of such models based on archaeological data. Barcélo claims that models should be embraced as they offer the means to represent features of a concrete or abstract entity as opposed to mere illustrations that have been previously relied upon.3 Indeed three-dimensional modelling offers a level of control and an ability to reconstruct past built environments in an entirely new fashion. Inexpensive, fully three-dimensional environments can be built based upon factual data. The benefits of these models are numerable and range from an educational resource that can be employed by educators and museums alike, to complex models designed to address specific questions that, if asked of the archaeological evidence, jeopardises the integrity of the site. For example stress tests can be applied to virtual ancient bridges and similar structures.

The focus of this project is on the creation of a model for display in a museum. Sanders writes the following of models generated for such contexts:

'Our software becomes a dynamic medium for promoting awareness of past civilisations, understanding of different cultures, and appreciation of different places, people and their cultural heritage'.4

This is an ideal scenario where the modelling process will be an accepted tool for the dissemination of information. For this purpose Kantner promotes simpler models designed specifically for pedagogical use.5 Such an approach was well-suited to this project as it was created for a learning environment with a definite focus on knowledge-transfer. Furthermore time constraints and the scale of this project, being part of M.Sc. study in Archaeological Computing at the University of Southampton, would have made anything but a 'simple' model unrealistic. A volumetric representation with limited detail, for example simple textures, was sufficient. This is not to say it was oversimplified to the point of jeopardising the nature of the collected data. Archaeological excavation data were used, and, where available, ground plans were used to 'extrude' aspects of the built environment of the medieval town. Where structures remain they were recreated as faithfully as possible with the date provided. They were not intended to be photorealistic representations; rather they are geometric primitives manipulated to be an adequate representation of reality; it is not the intention of this project to mimic reality. Niccolucci is quick to point out that virtual visualisation does not need to faithfully recreate reality to be a successful tool for archaeology.6 In this case it will be sufficient for the purpose at hand and lessen the computation involved, something important as the museum's resources are limited.

With any model it is easy, particularly when simplicity is discussed, to misrepresent the data. This is an even more contentious issue when remains are incomplete or non-existent as this often requires leaps of faith and differing levels of assumption. There is often a perceived hypersensitivity towards such leaps of faith by sections of the archaeological community. However, it is important to note that in the creation of such models we are not destroying the data or misleading anybody, assuming the modeller adopts an open approach to the available data and assumptions made. In essence we are merely using technology as a means of throwing around ideas. As long as the modeller is honest with the data used and the conclusions drawn, there can be no criticism of the process. Indeed it is possible to portray levels of certainty in models; for example colour-coding aspects of the model. In this project, as it intends to represent a hypothetical appearance of the town in 1454 using colours to separate out aspects of the model would be inappropriate. Therefore the ground plan has been colour-coded to represent the origin of the data for a particular aspect of the town (see Appendix 1) and also a table has been created to document levels of certainty (see Appendix 2). All this supplementary data will be provided alongside the model as it is important to present the model faithfully to visitors to the museum. Furthermore in the spirit of collaboration, feedback will be encouraged. Of course it would be possible to merely portray what is known, but that would not be as useful as a resource that attempts to place the archaeological data that remains in its original context. Modelling the data as they now appear would be very restrictive and of far less use. Indeed the purpose of models should be to portray information to the human eye that is difficult to perceive or imagine. This project attempted to construct medieval Southampton as it may have looked in 1454; uncertainty is inherent but not fulfilling the project remit due to such uncertainty would have been an exercise in futility.

Methodology

Data Collection and Validation

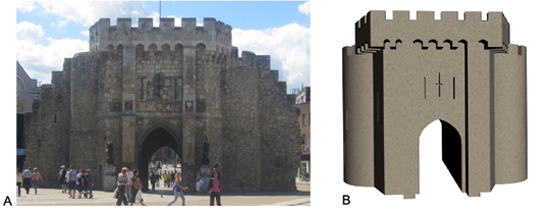

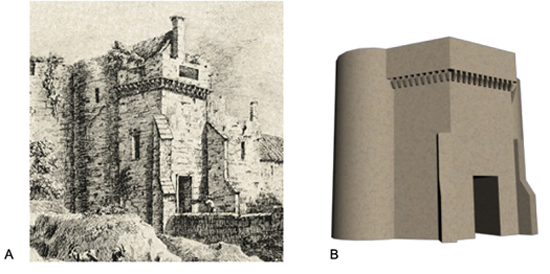

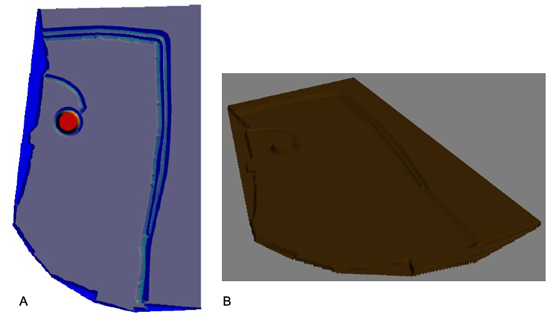

Before it was possible to begin modelling it was necessary to assimilate various different sources. These consisted of archaeological plans, historical records, map data, paintings and illustrations, as well as secondary sources. Historical records and secondary sources were used when archaeological plans were absent, and also to validate contemporary structures and remains. This was necessary as many surviving medieval buildings in Southampton have had numerous building phases. Histories are an excellent way of identifying aspects of the physical structures that would have been present in 1454. Indeed there are many buildings that survive well including 58 French Street, St Michael's Church, Wool House as well as many defensive elements including the Bargate (Fig. 2A) and sections of the town walls. These buildings were modelled by taking photographs and scaling them to match archaeological ground plans of the sites (Figs. 2A and 4A, and Figs. 2B and 4B).

Fig. 2. Bargate A. Photograph of the exterior. B. Finished model.

Fig. 3. Eastgate. A. Drawing made shortly before its demolition (after Platt 1973:48). B. Finished model.

Buildings that are extant from the archaeological record are not always absent from local histories. For example it was possible to create a ground plan of St John’s church that was destroyed in the seventeenth century, from Davies’s history of Southampton.7 The church was then built up conjecturally based on these acquired dimensions. The historical record also allowed for the acquisition of building plans and sketches. For example it was possible to create a good representation of St Laurence church based on archived plans and a sketch. Eastgate was created solely from a painting made in the nineteenth century (Fig. 3) and it was possible to reconstruct the Watergate based on a similar representation and an archaeological plan created from the remains of the gate. These sources, and many others, were of great use and the modelling process used them all in order to create the best representation of the medieval town possible.

Fig. 4. 58 French Street. A. Photograph, B. Finished model.

Creating a Town Plan

The first stage in creating a model of the town was to bring together the different sources to produce a plan of the town that would be more accurate and reliable. This was done using AutoCAD. The data sets in question were map data, archaeological plans retrieved during the research phase, and the Terrier. Geo-references were added to the Terrier, based on map data; correlating points between the two data sets were used to do this. Archaeological plans were then imported, scaled according to their scale bars or points of reference on the map data. The digitisation process employed when creating the plan was hierarchical in nature. It made assumptions about the accuracy and utility of the data. Digitisation assumed the archaeological plans to be the most reliable, followed by the map data. The Terrier was only used in the absence of archaeological data, map or planar. An exception to this came on the stretch of wall at the rear of the Friary; due to the poorer quality of the archaeological plan for this area map data was used. It was inevitable that these data sets would not correlate precisely and there would be discrepancies and a need to tie, for example, digitised aspects of the Terrier and map information. In addition other assumptions had to be made; for example the need to mirror the surviving drum tower of the Watergate to create the non-surviving tower. It is immediately apparent upon viewing the plan how it has been put together (see Appendix 1); dark blue denotes digitised sections based on map data, light blue - archaeological plans; green - Terrier, and magenta - conjectural based on assumption.

Building the Model

The building of the three-dimensional model was done exclusively in 3D StudioMax (3ds Max) 9. Once the plan creation process was completed, as described above, it was broken down into different sections.

These ranged from an individual tenement to the town walls. These plans were then imported into 3ds Max in order to provide a blueprint for the creation of a representative model of that particular aspect of the town. 3ds Max allows for the creation of complex models from simple geometric primitives. Through the manipulation and building of relationships between objects it was possible to create three-dimensional models of aspects of the town. Once a section of the model had been made, a group was created and named accordingly. For example, primitives making up 58 French Street were placed in a group called '58 French Street'. These individual elements were then externally referenced into a master file to allow them to be joined to create the town – in this manner file sizes were kept relatively manageable. The complexity of these models is not excessive and rather provides a good simple representation of the modelled town element. More complex modelling was not possible due to both time and data-enforced limitations.

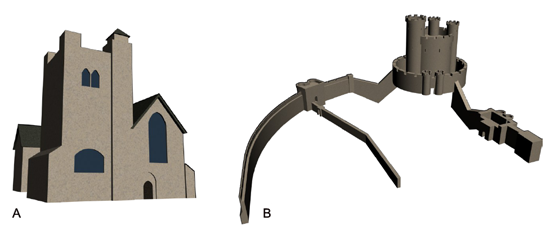

Fig. 5. A. Model of All Saints church. B. Finished model of the castle.

For a representation of the medieval town to be presented effectively it was necessary to create a terrain. Due to the lack of any sort of survey for the town in the medieval period, and poor resolution data for the modern day it was not possible to create a truly accurate terrain. Instead, and in keeping with the simple educational methodology, a terrain was created based on the Terrier in order to highlight the defence mechanisms employed within the town; namely the ditches surrounding the walls and similar precautionary measures at the castle. It was also possible to show that the south and west of the town would have met abruptly with the sea. Due to technological problems with ArcGIS it was necessary to create a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) using digitised data from the Terrier with software called Global Mapper. A 1.5m resolution DEM was created (Fig. 6A) and then imported into 3ds Max (Fig. 6B). As everything had been created using the same master source data it was not necessary to rescale or move anything as it was already geographically correct. Using a plug-in for 3ds Max called Vue 6 Xstream it was possible to create an atmosphere for the model to be placed within. This consisted of a sky, a sun and some clouds, which was done purely for presentational purposes.

Fig. 6 A. Digital Elevation Model built up based on the digitised plan. B. Generated terrain in 3D StudioMax.

As with other aspects of the modelling process materials were kept simple and designed to allow users to view a good, clear representation of aspects of the town. All materials were made procedurally rather than by draping images over objects. This is more aesthetically pleasing at high levels of zoom and also requires less computation. Furthermore applying such materials to objects

is a far more efficient process than working with image-based materials. Using various filters in 3ds Max it was possible to create procedural materials for black and white paint, stone, wood, fencing, slate, grass, glass, a basic ground material, and the terrain . These are clearly representative of their real-world equivalents even at high levels of zoom.

The Decision Making Process

Throughout the modelling process it was necessary to make decisions that have implications for the finished product. A number of these issues will be discussed in this section. The Terrier is essentially a two-dimensional version of what the project intends to achieve. Plots were created by the author in order to create a model of how the town could have been laid out. In creating the Terrier Burgess had to make decisions along the way; for example, what size to make cottage and tenement plots. As this project is focused on using the available archaeology in the creation of a model of the town it was possible to ascertain actual plot sizes; which facilitated the creation of generic buildings that could be used throughout the town. This was achieved with data obtained courtesy of Oxford Archaeology, from their recent excavations in the French quarter. This was a particularly useful dataset as the area south of Polymond Hall showed the layout of both tenements and cottages and was, generally, coherent with the location of the plots as detailed by the Terrier. This was heartening as it both justified the use of the Terrier as a tool for defining the town layout, and allowed the plan built up by Burgess to be further refined and strengthened.

Fig.7. Buildings created based on Oxford Archaeology's plan of English Street situated on the block north of Brewhouse Lane.

Using these data three types of cottage, and five types of tenement were created; excavation plans were used for the ground measurements. Analogy was used through research on medieval houses and evidence from surviving houses in Southampton were both used as inspiration and as points of reference.8 These buildings were then placed throughout the town depending on the tenement type and plot size, as suggested by Burgess. Plots were kept as much as to Burgess's plan as possible, but it was often necessary to adjust plots to fit buildings. A consistent problem was the size granted by Burgess to cottages, which was often very generous compared to the ground plans excavated by Oxford Archaeology. There are problems with using generic buildings and this is grossly over-simplifying the town. However, given the lack of above-ground evidence for most of the town, it was deemed wholly appropriate to use such buildings for the model. When it came to modelling God's House Hospital the large plot allotted to them by Burgess, and the lack of archaeological evidence for the greater part of these sites presented a problem. Research shows that it was known to a degree what buildings would be present in God's House Hospital. Therefore this information was used when creating the model of the complex. Inspiration was then taken from a conjectural sketch of the town (Fig. 1B) and a garden was placed in the centre of the complex.

As with God's House Hospital complex other buildings required decisions to be made; for example, halls and warehouses needed to be created. Simple structures were constructed, and height data was gauged from similar buildings that survive today. For example, warehouses were sized according to Wool House, and halls sized according to the heights of large town houses such as 58 French Street. It was necessary to scale some versions of these buildings down as Burgess details some warehouses as much smaller than others. Common sense was therefore employed and such buildings were based on similar structures and then scaled as necessary. Canute's Palace was converted into a warehouse in the thirteenth or fourteenth century; it was thus modelled in this role. The door was placed where excavation showed it to be, and the rear window mirrored and placed on the front. The final major problem was how to represent the shape of medieval plots as laid out by Burgess (1976). Excavation had shown that the buildings took up the front of the plot, but did not occupy a substantial amount of it. Therefore gardens were created; it is likely there would have been gardens for a large number of the tenements as the Terrier-derived plan seems to have accounted for. It was not known what these gardens may have held structurally, if anything, so low fences were erected to mark out the plots and a grass material places on the ground. The fences were given a light wood material to fit in with the overall style of the model. To further anchor the fact that these are gardens trees were added to some of them. These areas were created as such to ensure clear and simple definition of the medieval plots.

Presenting the Model

Once the model was created it was necessary to create stills for presentation within the museum. These were done of individual elements of the town and the town as a whole. Different renders were also produced based on the level of certainty for elements of the town. For example, renders were produced of the structures that stand today, including those based on archaeological evidence, and also renders of a conjectural complete town. In this way the audience will be able to differentiate between conjecture and more factually based information. Animations will be created in the future of the model; indeed these animations have been set up and will be rendered as soon as possible.

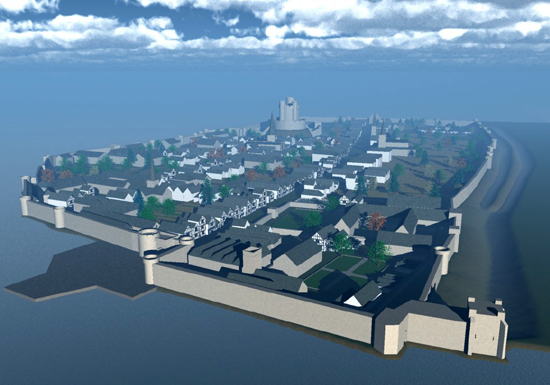

Fig. 8. A still render of the finished model of Southampton as it might have looked in 1454.

Ongoing Work

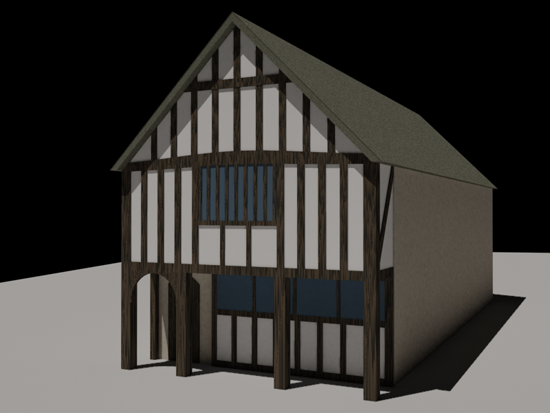

The created model was by necessity simplistic. It is intended that the model is improved over time and enhanced with any new data when these become available. Future work will include higher quality output; for example through the use of more advanced lighting techniques, as it has been the case with 58 French Street (Fig. 9). Interaction with the model is also envisaged to allow a greater level of engagement with a museum visitor than merely looking at images and videos. Indeed an example using 58 French Street has already been created using VR4MAX.

Fig. 9. Model of 58 French Street with advanced lighting.

Conclusions

The Archaeological and the Historical Record

The production of a plan of the medieval town based on archaeological data, the Terrier and map information, was not as straightforward as would have been hoped. Cohesiveness was discovered to be distinctly lacking in a number of areas which threw the Terrier's utility into question. The regularity adopted by the Terrier-derived plan, unfortunately, was borne out of necessity. Having only a street pattern and a list of tenements and buildings in a textual format meant that the transition from historical document to plan demanded a degree of assumption. In plotting remains based on archaeology and map data it became immediately apparent that the layout in the Terrier plan was somewhat misleading. For example, at the corner of Broad and English Street archaeological excavation has uncovered a tenement layout different to that set out by Burgess. A layout as discovered by excavation, however, would not be predictable based on the data within the Terrier. Burgess created the map from a historical document and in doing so chose a regular layout; indeed such a layout is the 'common sense' choice and the level of consistency made assumption and 'imagination' on the part of the author minimal. It is likely that other tenements did exist in less regular layouts, as suggested in Burgess's plan. Indeed the case mentioned is one of the only amalgamation of tenements excavated. The fact that this does not fit wholly with the plan is symptomatic of what is most likely a significant level of error.

Further problems arose from the Terrier as it only deals with rent-paying properties displaying other areas merely as vacant plots. Without the survival of the Duke of Wellington pub this building and its location in the town may have been lost as the Terrier lists the plot of land it locates as a vacant plot. Furthermore some buildings, recovered through excavation or that are surviving, appear not to have been documented in the Terrier at all. King John's and the house just south of this building, also joining onto the town wall, are not reserved a plot in the Terrier, but excavation has shown them to have been present in 1454. Indeed Canute's Palace in the south of the town appears to be in the middle of a street and have no designated plot, but again, it would have been present in 1454. Like King John's the discovery of these buildings overlaps with the tenement structure as suggested by Burgess's plan. Fortunately despite the lack of these structures in the plan there is still room in the plots they overlap for buildings to have been present. However, it is odd that these buildings were not included in the Terrier document and surprising that Burgess did not allow for such remains when compiling his plan. A further issue is with the Friary and God's House Hospital; these areas would have contained more than one building, but given the purpose of the Terrier they are treated as a whole; thus details of the separate buildings are lacking. Excavation on the Friary has shown that it would not have been merely one large building, as one could conclude from the Terrier-derived plan. Despite this, other remains, when plotted, do tie up quite well with the Terrier plan. 58 French Street, the Red Lion pub and Bull Hall are examples of such structures. Dimensions are sometimes misrepresented in the Terrier, but for a number of buildings there is a good level of coherence; St. Michael's church and Holyrood church being two further examples.

Excavation work by Oxford Archaeology also showed a section of the Terrier plan to be of a good degree of accuracy. Furthermore without the Terrier, and Burgess's plan made from it, we would have little idea of the scale of development of the medieval town. The number of properties as detailed through the plan and subsequently the model produced show how the space within the walls was utilised. The Terrier, in the case of this work, also demanded questions of the surviving aspects of the medieval town and stimulated academic thought on these issues. For example, the Terrier details three towers on the west of the town that are not apparent from map data or archaeological data, despite the complete remains of the wall along this section of the perimeter. On closer inspection of the wall, indentations were found which suggest there may have been a further structure at three places along its length. By using the Terrier it becomes clear these were towers. Another example of how the Terrier is forcing the interpretation of the medieval town is the lack of archaeology and tenements in the north-west of the town. Indeed in the Terrier it is a blank expanse. It has been suggested by Dr David Hinton of the University of Southampton (personal communication) that this may have been an area left open as a 'killing ground' if an enemy breached the defences. Another possibility is it could have been an area for stables or agriculture.

This project relied heavily upon the work of others and their documentation of historical monuments and archaeological sites. From the use of a number of such sources a glaring omission became consistently apparent; the lack of height information. Even for buildings that stand today it is possible to obtain descriptions and ground plans but there is no height data or elevation plans published alongside. This was particularly troublesome given the fact the model was being produced in three dimensions. The ability to draw up accurate ground plans suggests a survey has been undertaken of existing structures; surely therefore it would have been possible to survey the whole site rather than just floor plans. Indeed the omission of such data produces a particularly flawed record of the site. It is not just surviving structures that would benefit from the recording of height data; those that survive partially also need to be recorded comprehensively. Canute's Palace survives to roof level and recording this height would be very valuable; an elevation plan even more so. The lack of these data in archaeological reports meant that gauging these height values was more difficult and much less accurate than if the values had been obtained from actual measurements through survey. Unfortunately this project did not provide the author with the time or resources to perform such a survey; therefore it was necessary to use photographic evidence coupled with known measurements (usually ground plans) in order to ascertain height values; hardly an ideal situation.

Impressions of the Modelled Town

The created model of medieval Southampton in 1454 can tell us a lot about how town planners made use of space. From a three-dimensional representation it is much easier to draw conclusions about the use of space within the town walls. The model further anchors the fact that the streets were crowded with tenements. The High Street's prominent position is clear and the cigar-shape of the street does indeed make a large area which would have been suitable for markets and other activities at the very heart of the town. Other streets feed off this main avenue. It is also clear that some areas were more affluent than others. Indeed there appears more crowding and a greater quantity of lesser tenements in the traditionally English north-east of the town than in the Norman hub of the town, the south-west; this had more open space for gardens and contained predominantly tenements and all of the large halls of the town.

The model allows appreciation of how prominent the notions of defence and religion were within the town. Regarding defences, the castle's presence was immense and most likely would have been visible from most areas of the town and clearly visible from outside the town walls. This was most probably a deliberate ploy to reflect the status of the town. The town gates were also impressive structures; particularly the Bargate and the Watergate. The modelled Eastgate does not look as sizeable as the Bargate but was still an imposing design; perhaps again this was more to reflect the status of the town than as a purely defensive tool. The model also highlights the regular spacing and intelligent placement of the towers. For example, a tower on the west town wall faces south thanks to a change in the walls direction; clearly this was designed to allow archers to fire south from this tower in the event of an enemy attack. Furthermore the prominence and importance of the sea can truly be appreciated from the model. Half of the town's perimeter was surrounded by the sea. Visually the view from incoming vessels must have been immensely impressive, with the fortressed town occupying the very edge of the land with its wharfage facilities jutting outwards. Such a position was ideal for trade and defence, and the model highlights this well.

The number of churches, their location and scale reflects the importance of religion within the town. The church of St Laurence is particularly interesting in that it is much thinner than the other churches in the town and is of a different design. This could suggest that it was built on a limited plot much like the tenements surrounding it. This would make this particular design a necessary choice. Indeed other churches in the town occupy much larger plots. The model suggests that St Michael's was the grandest church within the town and it would have been a very prominent landmark. This is hardly surprising as it was built in an area filled with affluent Norman traders and was named after the patron saint of Normandy; it may too have been built to be a significant symbol of the Norman presence in the town. These are merely initial observations; it is hoped that the creation of the model will encourage museum visitors to postulate such questions regarding medieval Southampton. As aforementioned the openness of the project and the data means that at any time it can be interrogated and added to as new ideas and facts are realised.

Notes:

1. Burgess, L.A. (1976), The Southampton Terrier of 1454, London: HMSO.

2. Hermon, S. and Fabian, P. (2002), 'Virtual Reconstruction of Archaeological Sites: Some Archaeological Scientific Considerations', Virtual Archaeology. Proceedings of the VAST Euroconference, Arezzo 24-26 November 2000. Niccolucci, F. (ed), Oxford: Archaeopress, 38.

3. Barcélo, J.A. (2000), 'Introduction', Virtual Reality in Archaeology, Barceló, J. A; Forte, M. and Sanders, D.H. (eds), BAR International Series 843, Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 9.

4. Sanders, D.H. (2000), 'Introduction', Virtual Reality in Archaeology, Barceló, J. A; Forte, M. and Sanders, D.H. (eds), BAR International Series 843, Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 37.

5. Kantner, J. (2000), 'Realism vs. Reality: Creating Virtual Reconstructions of Prehistoric Architecture', Virtual Reality in Archaeology, Barceló, J. A; Forte, M. and Sanders, D.H. (eds), BAR International Series 843, Oxford: Archaeopress.

6. Niccolucci, F., (ed) (2002), Virtual Archaeology. Proceedings of the VAST Euroconference, Arezzo 24-26 November 2000, Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 4.

7. Davies, J. S. (1883), A History of Southampton, Southampton: Gilbert and Co., p. 372.

8. Grenville, J. (1997), Medieval Housing, London: Leicester University Press. Quiney, A. (2003), Town Houses of Medieval Britain, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Further bibliography:

Church Plans Online, published by Lambeth Palace Library.

Forte, M. (ed), (1997), Virtual Archaeology: Re-Creating Ancient Worlds, New York: H.N. Abrams.

Platt, C. (1973), Medieval Southampton: The Port and Trading Community, 1000-1600, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Platt, C. and Coleman-Smith, R. (eds) (1975), Excavations in Medieval Southampton, 1953-1969, Leicester: University Press.

Reilly, P. (1990), ‘Towards a Virtual Archaeology’, Computer Applications in Archaeology, Lockyear, K. and Rahtz, S. (eds), Oxford: Archaeopress BAR International Series 565, pp. 133-139.

Southampton City Council

© 3DVisA and Matt Jones, 2008.

Back to contents